Abstract

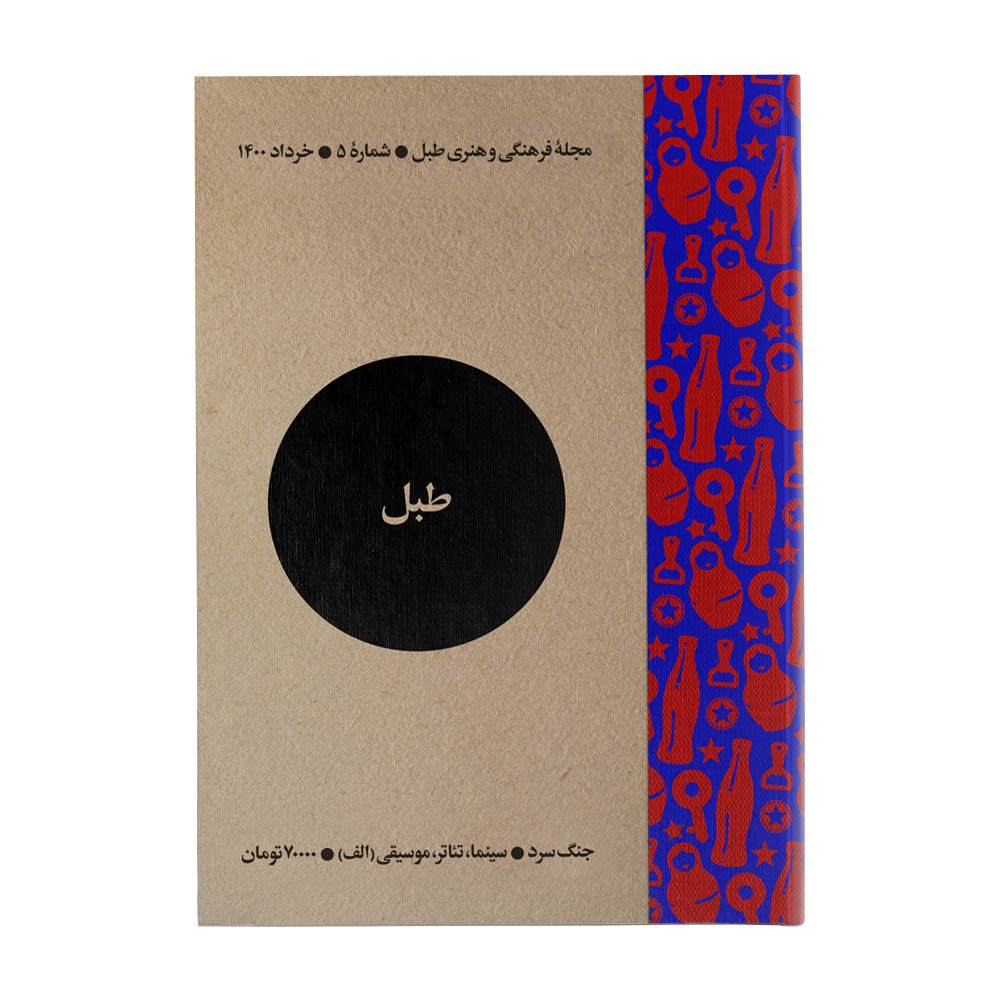

The fifth issue of Tabl magazine, published in June 2021 with ten articles and two interviews, explores Iranian cinema, theater, and music during the Cold War.

The first article briefly introduces the book Iranian Cosmopolitanism: A Cinematic History written by Golbarg Rekabtalaei, which deals with the history of Iranian cinema from its inception until the 1979 Revolution. Rekabtalaei reinterprets the experience of Iranian modernity, which she believes is made distinct by its cosmopolitanism, through the perspective of cinema. The author of this article introduces the book in three parts: 1. Iranian cinema during World War II; 2. Iranian cinema after World War II; and 3. Cinema and westernization: reactions to the cinema during the political turmoil.

In an interview with Mohammad Tahaminejad, conducted by Mahsa Tehrani, Tahaminejad discusses “the Warm Cinema of the Cold Years in Iran.” This conversation covers various topics, such as different periods of the history of Iranian cinema, prominent people and films from these periods, political tendencies in the cinema of the 40s and 50s, the formation of different views and approaches taken by filmmakers, the activities of the Iran-America Society and the Iran-Soviet Society for Cultural Relations, how American and German cinema came to be publicly screened in Iranian cinemas, how dubbing was linked to political interests, and finally, foreign investments in Iranian filmmaking.

The article “The Impact of the Cold War on Iranian Cinema,” written by Saeed Nouri, deals with the “visual elements of the Cold War in Film-Farsi.” This article begins with a study of the early years of Iranian cinema before World War II, which included no signs of the east-west conflict, and examines factors that played an important role in attracting viewers in the early years of cinema. The study continues with a review of the reasons behind the despairing atmosphere and bitter endings of the 1950s films, together with documentaries and educational films of the second half of this decade, the policy of making more light-hearted films in the 1960s, the return of bitter endings to the 1970s films until the Revolution, and post-revolutionary ideological cinema.

In his article “Iranian Cinema and the Cultural Cold War”, Mohammad Sarvizargar discusses the conflict between left and right in Iranian cinema in three scenes: the conflict between pro-Russian and British forces at the emergence of Iranian cinema (Qajar era); the conflict between American cinema and the cinema of the Soviet Union during the Cold War (Pahlavi era); and the continuation of the Cold War-related cinematic representations in the new millennium under the title of “Age of Hot Wars” (post-September 11th). The author argues that cinema has been a vehicle for advancing political and economic strife, which he refers to as the “Cultural Cold War.”

In another article, Mohammad Hossein Mirbaba reviews “Protest Figures” in pre-revolutionary cinema. Referring to a period in the history of Iranian cinema known as “New Wave,” he studies protest figures which were one of the most important and common components of films from this period. Figures, who rose from the heart of society and began to oppose the status quo, such as the main character in Gheysar, Ebi in The Beehive, and Hashem in Brick and Mirror. Moreover, he examines how, despite the impact of the Cold War on Iranian political and social relations, as well as literary and artistic intellectual currents, cinema and its protest figures were less affected by the Cold War-related sociopolitical confrontations.

In the next article, Ahmad Zhirafar explores the role of dubbing in propaganda and political influence through cinema and commercial newsreels, which was part of the agenda of countries like the Soviet Union, Germany, and the United Kingdom. He focuses particularly on Russian newsreels that were sent to Iran with Persian dialogue. This was one of the first acts that drew the attention of filmmakers to dubbing and Persian dialogue as a means of attracting more audiences.

Massoud Kouhestani-nejad focuses on the impact of the Cold War on theater, which like other cultural and artistic realms in Iran, was the scene of conflict between the eastern and western forces. The theater was used as a place to display and promote the characteristics, cultural symbols, and customs of the home front while questioning the social and cultural values of the other. The article reviews the activities of cultural and artistic associations in theater between 1946 and 1978.

“The Skull that Wanted to Be Restored” is the title of an article by Araz Barseghian on the subject of Iranian theater during the Cold War, covering the period from 1953 to 1963. The purpose of this article is to provide a formulation of the progress of theater in the social context of Iran. Following the 1953 coup d’état, plays had very little political stance, so it is not feasible to study the effects of the Cold War just by analyzing their titles. Instead, the article seeks the impact of the Cold War on Iranian theater by reviewing its compatibility with internal and external conditions.

“Iranian Leftist Theater” is the subject of an interview with Reza Soroor. Referring to the beginnings of the leftist theater in Iran, and examining the activities of Tudeh Party and the works they translated and performed, Soroor concludes that there was a contradiction between the beliefs and actions of the members of Tudeh Party in theater. Therefore, he believes that the Tudeh Party was unsuccessful in its political exploit of the theater. In addition, the activities of Gholamhossein Saedi, as the most important representative of Iran’s leftist theater, out of the Tudeh Party, the opposition to leftist theater, the Pahlavi government’s failed attempts of politicizing theater, and the absence of literary criticism due to the nonexistence of theoretical resources, are also discussed in this conversation.

Before the emergence of cinema and television as the main entertaining media, the ballet was very popular among the masses and social elites, as it formed a part of the mass culture of the time. When ballet, which is known as a non-ideological European art form, blended with Eastern components, it becomes an orientalist medium that reflects a society’s position and approaches towards the east-west dichotomy. By examining Diaghilev’s “Scheherazade” ballet as a case study, in the article “From Russian to Iranian Ballet,” Firuza Melville discusses the evolution of orientalism in ballet and studies the connection between this ideology and the so-called “oriental” literary model.

In his article “Cossacks without Boots,” Amir Bahari discusses the influence of Russian music and musicians on Iranian music. Russian nationalist music had a significant impact on Iranian’s and in a way, initiated a nationalistic tendency in Iranian music. In the 1950s and 1960s, another type of Russian music called Chanson reached the people of Guilan, and the author, despite other researchers, believes that this type of music had a more Russian influence than French.