Abstract

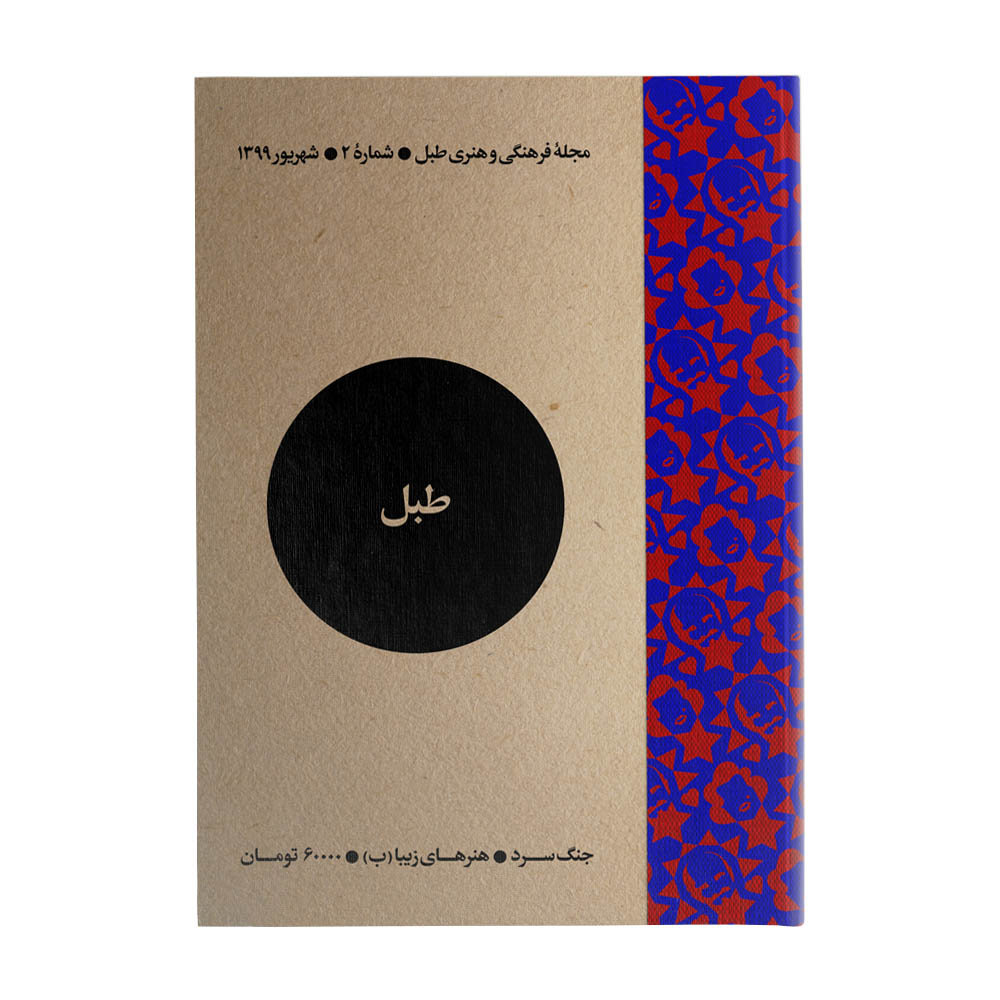

Tabl Magazine’s second issue, published in September 2020, following the first issue, studies Cold War with a focus on Fine Arts. Through seven essays and four interviews, this issue tries to explore the Cold War’s influences on literary and art movements and the emergence of new trends in the socio-political context of Iran.

Following the topics carried out in the first issue, namely the Report of the Iran-Soviet Society for Cultural Relations and the Iran-America Society and their impacts on the artistic movements and their circumstances, the second issue of Tabl Magazine attempts to introduce and describe the ups and downs faced by the Iran-Soviet Society for Cultural Relations, its activities in different cities, the fall of the Society in 1954, and the limited resumption of its activities until its permanent closure in 1983.

At the time of a relative decline in the influence of the above-mentioned Societies, and due to the success of Iranian modern literature and art in the early thirties, after the fall of Reza Shah’s dictatorship, the theoretical foundations of art and the principles of literary and artistic schools in the country was proposed for the first time. This led to the emergence of three main movements with various trends, namely Socialist Realism, Critical Realism, and Modern Nationalist Art, which shaped the artistic and literary life of Iran in the coming decades. This issue of the magazine describes the development of these three movements.

Through the examination of two distinct points of view, namely optimistic and pessimistic, the history of the formation and origins of the Fulbright U.S. Student Program in the world an Iran, during the postwar period, is also examined in this issue. The program was shaped, on the one hand, in a context where the concept of the Dialogue of Civilizations and the universal peace was gaining importance, and on the other hand, given the United States need to reproduce a system of power and wealth in the context of universal inequality.

Despite being an important subject of study, architecture has been hardly examined in the context of the Cold War. Therefore, an interview was conducted with Kamal Kamouneh, focusing on the impact of Western views and education on the professional and academic atmosphere of Iran.

A description of Reza Shah’s reformations, which are based on nationalism, archaism, and modernism in the fields of education, culture, society, and religion has been also studied in one of the articles. Reza Shah aimed to dismantle traditional systems and establish a modern and uniform Iran. It was in this context that Tehran’s first Biennale in 1958 led to the government’s recognition of the modernist movement. In this regard, Iran’s positive relations with the west and its avoidance of communism, as well as the west’s exotic view towards Iran, led to the creation of the Saqqakhana Movement. This Iranian movement influenced western and Iranian tastes and gained a special position that was maintained for many years, even after the Islamic Revolution, in a monophonic atmosphere.

At the same time, in this very atmosphere, the increased income from oil exports allowed the government to provide Farah Diba (the queen of Iran) with funds for art development. Therefore, it was made possible for the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art to exhibit works by pop artists, such as Andy Warhol, alongside other international leading artists, including Jasper Johns and David Hockney. It is assumed that this exhibition was inspired by the Guggenheim and the Museum of Modern Art in New York, after the travel of Shah and Farah to the United States, as well as the “Seven Thousand Years of Iranian Art” exhibition in Paris. The criticism that Andy Warhol received for a period of his career when he got acquainted with the Pahlavi family, and the commission he received for portraits of Farah, Shah, and Ashraf, that were similar to his collection portraits of other political figures, are also studied in this issue.

Another essay focuses on the influence of the leftists on Iranian modern paintings and the Revolution. In addition to exploring the definition of the leftism, as the dominant political and cultural discourse that encouraged the Islamic Revolution, this investigation also describes the intellectual and aesthetic trends of leftism, the emergence of Socialist Realism and the revolutionary or the committed art in literature and painting, and their fate after the Islamic Revolution.

The second issue of the magazine also includes Parviz Habibpour’s experiences and observations on the activities of the Council of Iranian Authors and Artists in a decade before and shortly after the Revolution.

Leftism and its reflection in the discourse of visual arts after the Revolution is also analyzed, as part of which, the intellectual and visual characteristics of this ideology, as well as the relationship between form and content are examined. This ideology ultimately led to the denouncement of formalism and the consolidation of realism, together with an attempt to create original, committed, and revolutionary art to support the Revolution and the struggle against tyranny. After the 1980s and the Iran-Iraq war, this ideology led to romanticism and poetic expression of concepts such as martyrdom and jihad.

The last part of the second issue includes an interview with Shahrouz Nazari, who focuses on the Cold War and its impact on visual arts and covers various topics, such as political and committed art, as well as the confrontation between the leftism and nationalism led by the development of the idea of American hegemony.