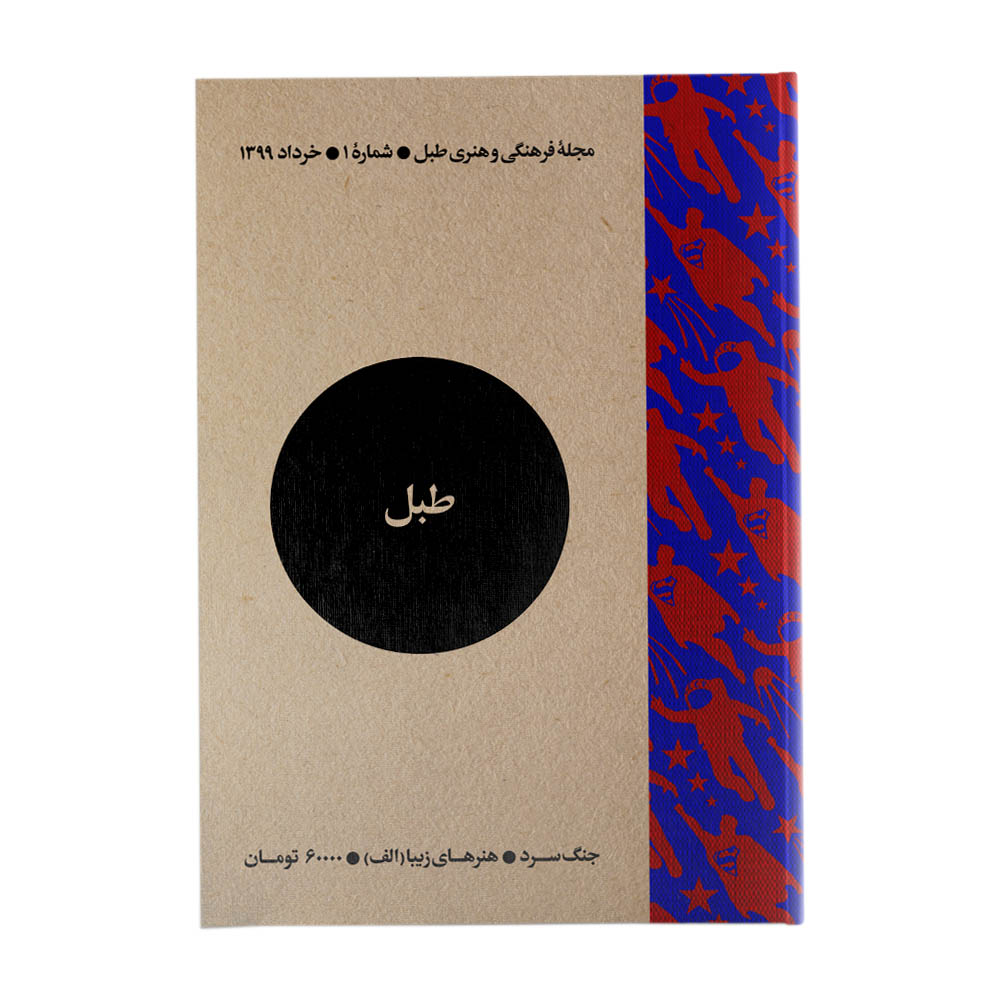

Abstract

Tabl Magazine’s first issue, published in June 2020, studies Cold War with a focus on Fine Arts. Through ten essays and an interview, this issue tries to describe the political and geopolitical position of Iran, between and after two World Wars, attempting to reveal the reasons for Iran serving as a context for the confrontation of eastern and western forces.

During its long-lasting history, Iran, being among the most powerful countries in the world or the region, benefited from the existence of barriers between itself and rival powers. With losing its former power and position and the emergence of new regional powers since the late 18th century, Iran transformed into a barrier itself; a buffer zone between England and Russia, during the so-called “Great Game” confrontations. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, after few years of detente between England and Russia over the years between two World Wars, this situation resumed with a different approach.

The occupation of Iran by the Allies led to the abandonment of Iran’s policy of neutrality. When Reza Shah abdicated power, the government’s political approach changed. Therefore, the opponent forces of the Soviet Union, on the one hand, and Britain and the United States, on the other hand, temporarily put aside their existing rivalries and historical differences and invaded Iran to defeat a common enemy, namely Germany. With the end of World War II and the fall of Nazi Germany, however, the rivalry and conflict between the eastern and western forces resumed.

Cold War had been started in Iran before the World Wars. Its development, however, during the post-World War II time, in contrast to the previous eras was significantly different. One of the main differences was the final decline of Britain and the establishment of the United States as a global power after World War II. It was during these years that the United States—the largest Western party in the Cold War and one of its main actors—gained a major political power. Moreover, the difference between the rivalry of the western and eastern powers in the years between the two World Wars versus the previous eras was the dormant and inactive aspects of their confrontations. In general, what distinguished the Cold War from periods of political confrontation was that it had a profound and lasting impact on the involved societies, as it challenged both popular culture and science, through shaping and transforming them. Accordingly, in addition to their military presence, the forces of the Allies set up societies to promote cultural relations with foreign countries. In 1925, the United States’ government established the Iran- America Society for Cultural Relations, but the Society’s activities began in earnest in late 1942. The British government also officially inaugurated the Iran-UK Society for Cultural Relations in July 1943. This society had been previously active in Iran, albeit unofficially.

At the same time, that the Soviet Union also joined the rivalry and in 1943, opened a branch of the All-Union Society for Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries (VOKS) in Tehran, which was not active. In May 1944, however, the Iran-Soviet Society for Cultural Relations established and worked independently.

Moreover, this issue covers notable topics including the Report of the Iran-Soviet Society for Cultural Relations and the Iran-America Society and the impact they might have had on the status and the situation of the fine arts and archeology during the Cold War. To this end, this issue studies the innovative role of the Iran-Soviet Society for Cultural Relations during its heyday in organizing, support, and holding the first fine arts exhibition in 1946. This exhibition, which was curated by Maryam Firooz (President of the Society) and held at the palace of Shahpour Gholamreza, was very well-received by the audience and was followed by the 1950, 1952, and 1953 exhibitions, held at the Society’s hall.

The dependence of the Iranian 20th-century modern art on the Iran-Soviet Society for Cultural Relations led to several changes in the professional life and the position of emerging artists such as Hossein Kazemi, Jalil Ziapour, as well as Habib Mohammadi and his students; which is also among the topics covered in this issue. This issue also includes articles on the role of the Iran-America Society, as an important weapon for the United States in achieving its political goal of preventing the domination of the Soviet Union and strengthening Iran’s orientation to the West through Truman’s Point Four program, and its impact on the production of documentaries, films, textbooks, children’s magazines, and comic strips. Moreover, in an interview with Masood Koohestani Nejad, the impact of the 1953 Iranian coup d’état on the activities of these two societies is examined.

In addition to the above-mentioned subjects that concentrate on the prevailing movements of three decades prior to the Islamic Revolution, this issue attempts to portray lost figures of Iranian cultural history during the Cold War, with a focus on the second Pahlavi era, including Assyrian, Azeri, Armenian, and Jewish elites.